Ever felt like the odds were stacked against you? That feeling of being the underdog isn’t just a fleeting emotion; it can profoundly shape your thoughts, decisions, and the risks you’re willing to take. We often hear about the psychology of the powerful, but what about the mindset of those with less influence? This article dives into “The Underdog’s Mind,” exploring the psychological landscape of lacking power. We’ll examine how this state influences choices, from everyday decisions to significant life risks. Drawing parallels from studies like the rigged Monopoly game, we’ll uncover the often-overlooked cognitive and behavioral shifts that occur when power is scarce. Get ready to see an insightful infographic summarizing key impacts later in the article!

Defining the “Underdog”: The Psychology of Powerlessness

We all encounter moments where challenges seem insurmountable, where the feeling of facing an uphill battle becomes palpable. This experience is often what is meant by being an “underdog.” But what are the underlying psychological processes at play in such situations? This isn’t merely about the external circumstances; it’s about the psychology of powerlessness, a state that can profoundly influence self-perception and interaction with the world.

So, what does it mean to be psychologically powerless? At its core, psychological powerlessness involves a perception that one’s choices have little impact or that outcomes cannot be influenced, regardless of effort. It’s this pervasive feeling of having a reduced sense of control over one’s circumstances. This state isn’t necessarily about an objective absence of power but rather the subjective experience of lacking it. This low-power state can manifest in various life domains – in professional settings, personal relationships, or when confronting broader societal issues. For instance, an individual from a background where their contributions were consistently overlooked might describe the feeling as akin to shouting into the wind – a vivid depiction of psychological powerlessness.

Now, how does lacking power affect self-perception? This is a significant aspect. A persistent feeling of being at a disadvantage can erode an individual’s view of themselves. Doubts about one’s abilities may arise, self-worth can be questioned, and the idea of not being “good enough” can become internalized. This underdog mentality, if it becomes deeply ingrained, risks creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. If success is perceived as unattainable, effort may diminish, or an individual might capitulate more readily. The internal compass may begin to orient towards “can’t” rather than “can.” This phenomenon can be observed in educational contexts, for example, where students who are labeled as not proficient in a certain subject may internalize this belief, and their performance subsequently reflects it, even if their underlying potential is significant. Their self-perception shifts due to the feeling of lacking power or aptitude in that specific domain. And, as one might expect, there are definitely common emotional responses to being in a low-power position. Consider the emotional sequelae of feeling unable to alter one’s situation. Frustration is a frequent response. A sense of anxiety or a heightened awareness of threats may also develop – a metaphorical vigilance stemming from perceived vulnerability. Studies, such as those examining experimentally induced low social status, have indicated that participants in these low-power conditions can report diminished feelings of pride and powerfulness. This is understandable; if one does not feel in control, it is difficult to feel proud of the outcomes. Sometimes, this can even contribute to a potential for learned helplessness, where repeated experiences of powerlessness lead an individual to cease attempting to exert control, even when opportunities for agency present themselves. It’s a challenging cycle to interrupt.

How do social experiments like the rigged Monopoly game illustrate powerlessness?

This is where the dynamics become particularly clear and illustrative. Social psychologists, such as Dr. Paul Piff, have employed ingenious experiments to demonstrate these phenomena in action. In the well-known rigged Monopoly game, one player is designated as “poor” from the outset – possessing less money and fewer advantages. They are, by experimental design, placed in a position of powerlessness within the game’s context. Researchers observe not only their inevitable loss but also how the experience of being the disadvantaged player, the one with no viable path to victory, mirrors these psychological states of powerlessness. They contend with a system structured for their failure. While the “rich” player in these games often exhibits increased dominance and attributes their success to personal skill, the “poor” player directly experiences what it means to have minimal agency or control over the outcome. These experiments, though games, offer a valuable window into the real-world psychological impact of being subjected to unequal power dynamics. They render the abstract concept of powerlessness tangible and observable, demonstrating how rapidly these feelings can manifest when situational factors dictate them. It serves as a potent reminder that outcomes are sometimes less about an individual’s inherent abilities and more about the power structures within which they operate.

The Underdog’s Dilemma: Choices Under Constraint

Having explored the subjective experience of being an underdog and the state of psychological powerlessness, let’s delve into a practical consequence: how does lacking power influence decision-making strategies? It’s one thing to experience certain emotions, but quite another to observe how these feelings tangibly alter the choices made, both minor and significant. This is the crux of the “Underdog’s Dilemma” – making decisions when options feel pre-limited, when operating under considerable constraint.

From a strategic viewpoint, an individual who perceives themselves as having less power, fewer resources, or diminished control over outcomes is unlikely to approach decisions in the same manner as someone who feels confident and in command. A common observation is that individuals in low-power situations may adopt more cautious or defensive decision-making strategies. They might exhibit less willingness to take substantial risks if the perceived probability of failure is high and the safety net appears inadequate or absent. It’s analogous to playing a game of chess when reduced to only a few pieces – each move demands meticulous consideration due to the minimal margin for error.

So, do underdogs make more cautious or more impulsive choices? This is a compelling question, and the answer is not always simple; it often depends on the specific context. As mentioned, a lack of power can sometimes lead to extreme caution, as individuals attempt to protect their scarce resources. However, there can also be scenarios where feeling powerless might precipitate more impulsive choices, particularly if an opportunity emerges that seems like a rare chance to escape existing constraints. This could manifest as a “what is there to lose?” mentality. The key factors here are often the perception of control and the availability of resources. If the system is perceived as inherently unfair, a high-risk, high-reward impulsive choice might appear more attractive than methodically attempting to operate within a system that is not trusted.

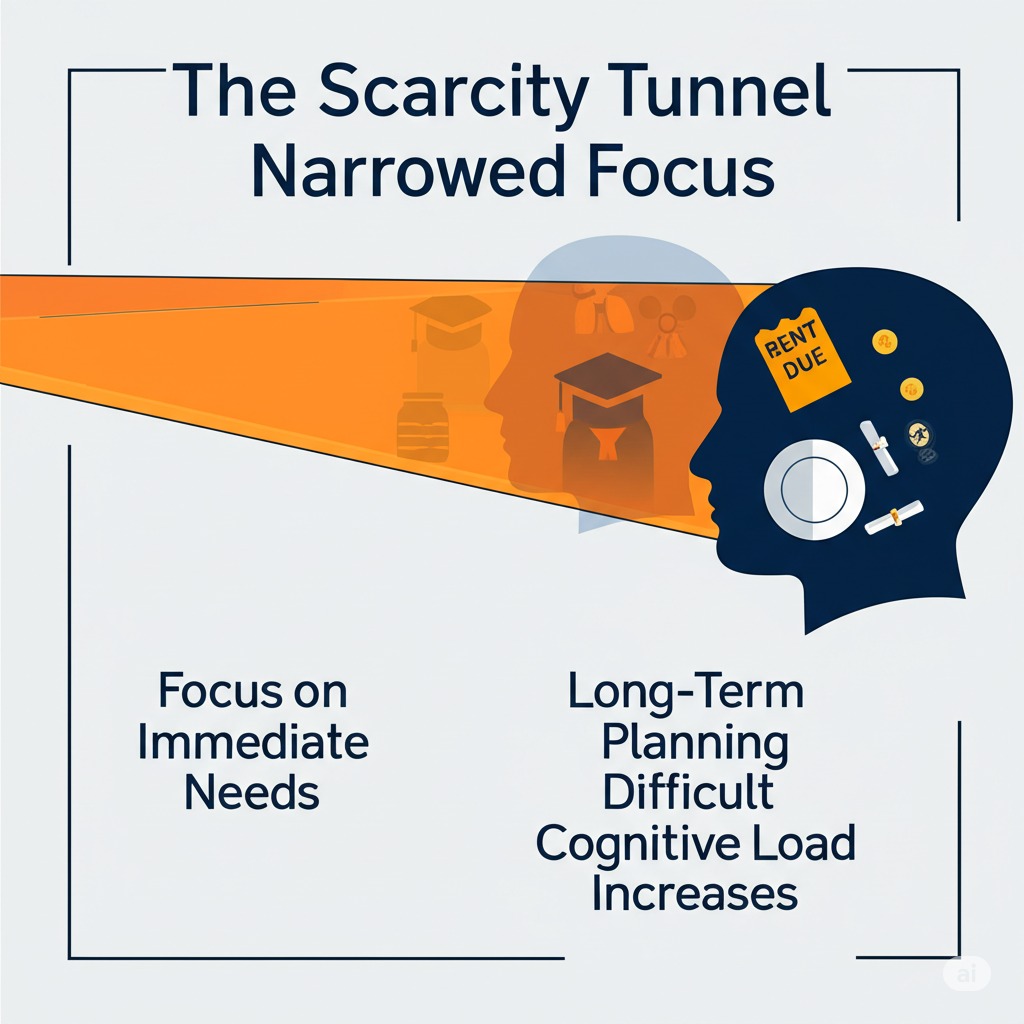

This brings us to another critical point: what role does perceived lack of resources play in choices? This factor is immensely significant. When an individual feels they lack sufficient resources – whether monetary, temporal, social connections, or even informational – it fundamentally alters their decision-making calculus. In the rigged Monopoly games previously discussed, the “poor player” commences with substantially less money. This initial scarcity immediately curtails their choices. They cannot acquire as many properties, they struggle to afford high rents, and their progression through the game is far more restricted. This dynamic is not confined to games; in real life, a perceived lack of resources can compel individuals to make choices they would not otherwise consider. They might be forced to select options that provide immediate relief, even if these are not optimal in the long term. This directly relates to whether lacking power can lead to a focus on immediate needs over long-term goals. Indeed, it can. When an individual is preoccupied with meeting immediate necessities, it becomes exceedingly difficult to engage in long-term planning. The cognitive focus tends to shift towards survival mode. Some research has even investigated how experimentally manipulated low social status can affect outcomes like acute energy intake, suggesting that in low-status conditions, there might be an increased prioritization of immediate caloric needs. This is not indicative of a moral deficit but rather a cognitive adaptation to perceived scarcity and uncertainty. If the source of one’s next meal (or opportunity, or measure of security) is unknown, the immediate, tangible option often takes precedence. For example, students who must work multiple jobs to fund their education often face choices about course selection or internship applications that are heavily constrained by their immediate financial needs, even if alternative choices might be more beneficial for their long-term career trajectories. It’s a perpetual balancing act, and the burden of these constraints shapes every decision. The “Underdog’s Dilemma” involves navigating these challenging choices, often without straightforward answers, and attempting to forge a path forward when the way is neither clear nor well-paved.

Risk-Taking Propensities: When Underdogs Gamble

This is where the dynamics become particularly fluid. It’s established that lacking power shapes how underdogs perceive the world and the choices they make under constraint. But what happens when it comes to taking chances? Are underdogs more risk-averse or risk-seeking? It’s a psychological balancing act, and the answer, as with many aspects of human behavior, is nuanced. One might assume that someone with less to lose would be more inclined to take risks, and this is sometimes the case. However, at other times, the fear of losing what little they possess can make them exceedingly cautious.

Consider a situation where an individual feels they are constantly struggling. On one hand, they might be very careful to maintain the status quo. Any minor loss could feel devastating. Thus, in many everyday scenarios, an underdog might be more risk-averse, opting for the safer, more predictable path to preserve their limited resources. They are, in effect, playing defensively. For example, a small business owner who built their enterprise from minimal resources might, for many years, exhibit extreme risk aversion, choosing conservative investments and safe bets because the prospect of losing everything is profoundly daunting.

However, there’s another dimension to this. How does the desire to change one’s circumstances affect risk-taking? This is where a shift towards risk-seeking behavior can be observed. If an underdog feels trapped in their current situation, and a high-risk opportunity arises that offers even a slight chance of significant improvement – a potential escape – they might be more inclined to take that gamble. It’s the allure of breaking free from constraints. Some research, such as Paul Piff’s 2012 PNAS paper, touched upon how lower-class individuals might sometimes be motivated to engage in certain behaviors, even unethical ones, if they perceive it as a means to overcome a disadvantage or level a playing field they view as unfair. This is not to suggest that underdogs are inherently unethical, but it underscores that the motivation to change one’s circumstances can be a potent driver, potentially altering risk calculations.

This leads to the concept of a “nothing to lose” mentality. Can this emerge in low-power situations? It certainly can. If individuals feel they are already at the lowest point, or that the current system offers no viable path for advancement, the potential downsides of a risky action might seem less significant compared to the potential upside. It’s a gamble driven by desperation, perhaps, but one stemming from a conviction that the status quo is intolerable or unsustainable. Consider historical underdog movements or individuals who pursue unconventional paths because conventional avenues appear closed to them. They might be undertaking substantial risks, but from their perspective, the risk of inaction, of remaining in a powerless position, is even greater. So, do underdogs take different types of risks compared to those in power? It appears they often do. Someone in a position of power might take calculated financial risks, secure in the knowledge of having a safety net. Their risks often pertain to accumulation or expansion. For an underdog, the risks might be more existential – aimed at changing their fundamental circumstances, gaining a foothold, or even challenging the system itself. These risks may be less about calculated financial investment and more about investing hope, effort, and sometimes personal safety, into something that could bring about a significant transformation. It’s not merely about the magnitude of risk, but the nature and meaning of that risk within the context of their lived experience of powerlessness. It’s a high-stakes endeavor when one feels perpetually disadvantaged.

The “Poor Player” Perspective: Lessons from the Rigged Monopoly Game

Let’s return to the insightful, and frankly, quite revealing, rigged Monopoly game that social psychologist Paul Piff and his colleagues have utilized to study these dynamics. Much attention is often given to the “rich” player, but what about the experience from the other side of the board? What was the experience of the “poor player” in Piff’s Monopoly experiment? Imagine participating in a game, only to discover at the outset that your opponent possesses twice the starting capital, rolls two dice to your one, and collects double the salary upon passing Go. The setup essentially preordains failure. That is the reality for the “poor player.” Their experience is one of immediate and conspicuous disadvantage. Now, how did the “poor players” react to the obvious unfairness of the game? This is where the observations become particularly illuminating. One might anticipate frustration, anger, or perhaps even a refusal to continue playing. While frustration was likely a component, Piff has noted that even in a game so transparently manipulated, the “poor players” often continued to play with sincerity; they persisted in trying their best within the severely constrained rules imposed upon them. They did not simply overturn the board and depart. This reveals something profound about the human tendency to engage, to strive, even when the odds are overwhelmingly unfavorable. It suggests an inherent desire to participate, to ascertain if perhaps, just perhaps, some positive outcome can be achieved or a minor victory secured.

Did the “poor players” show signs of distress or resignation?

While they may not have overtly disengaged, the psychological toll was likely present. The “rich” players, as established, often became ruder and less sensitive to the “plight” of the “poor, poor players”. Imagine playing a game where not only are the rules inherently unfair, but your opponent also becomes increasingly dismissive of your struggle. It’s a compounded adversity. While the specific emotional responses of the “poor player” are not always the central focus of every discussion of the experiment, it is reasonable to infer that feelings of frustration, perhaps a degree of resignation as the game progressed, and a keen awareness of their disadvantaged position were integral to their experience. They are, after all, subjected to a system designed to ensure their disadvantage, at least within the confines of that 15-minute game. So, what can the “poor player’s” behavior teach us about coping with systemic disadvantage? This is a critically important takeaway. The observation that many “poor players” continued to engage with the game, despite its inherent unfairness, speaks to a certain resilience or perhaps an ingrained societal script about “playing by the rules,” even when those rules are manifestly unjust. It highlights how individuals might endeavor to make the best of adverse situations, to find agency even in highly constrained environments. However, it also serves as a stark illustration of how challenging it is to overcome systemic disadvantages through individual effort alone when the system itself constitutes the primary barrier. The “poor player” can exert maximum effort, make the most astute moves available to them, but the structure of the rigged game renders their failure almost inevitable. It’s a powerful demonstration that individual grit and determination, while commendable, often cannot compensate for deeply entrenched systemic inequalities. The lesson is not that the “poor player” should simply capitulate, but rather that a critical examination of the “rules of the game” in broader society is necessary if the aim is to create genuinely fair opportunities for all.

Overcoming the Underdog Mindset: Strategies for Empowerment

Having explored the challenges and psychological landscape of being an underdog – the experience of lacking power, facing constrained choices, and navigating complex risk assessments – it’s important to shift focus. While the picture can seem daunting, this is not an immutable state. Can the psychological effects of lacking power be mitigated? Yes, there is strong reason to believe they can. Feeling powerless does not equate to being powerless, and there are certainly strategies to shift that mindset and reclaim a sense of agency. So, what strategies can individuals use to feel more empowered? This marks the transition from understanding the problem to actively seeking solutions. A crucial first step is awareness. Recognizing that the “underdog mindset” is a psychological response to a situation, rather than an inherent reflection of one’s worth or capabilities, is profoundly important. Once this is understood, it becomes possible to challenge it. Another key strategy involves focusing on controllable factors. When faced with large, systemic issues, it’s easy to feel that individual actions are inconsequential. However, identifying even small areas of life where one does have control and can make choices can begin to build a sense of efficacy. This might involve learning a new skill, improving a specific aspect of personal health, or taking charge of a small project. These “small wins” can be incredibly potent.

How can focusing on strengths and small wins help?

It’s about building momentum and altering one’s internal narrative. When in an underdog position, the tendency can be to focus on deficiencies. Yet, every individual possesses strengths. Identifying unique talents, skills, and positive qualities, and then finding avenues to utilize them, can be transformative. And those small wins? They serve as fuel for confidence. Each achievement, no matter how seemingly minor, reinforces the belief that one can effect change. It gradually erodes the feeling of powerlessness and begins to build a mental track record of success. It is a widely accepted psychological principle that acknowledging small victories builds a foundation for larger ones.

Now, does changing one’s environment or seeking support make a difference? The impact can be massive. Humans are social beings, and our environment and connections play a significant role in shaping feelings and behaviors. Persisting in an environment that constantly reinforces feelings of powerlessness makes positive change an arduous task. Sometimes, altering that environment, if feasible, or at least identifying niches within it where one feels more valued and capable, can be highly beneficial. And seeking support? That is absolutely critical. Build support networks. Connect with individuals who offer belief, upliftment, practical assistance, or simply empathetic listening. These networks can comprise friends, family, mentors, or support groups. The knowledge that one is not alone can be profoundly strengthening. Interestingly, some of Paul Piff’s broader research hints at the malleability of these mindsets; for instance, interventions such as exposing wealthier individuals to a brief video about child poverty could temporarily increase their compassion, suggesting that perspectives are not immutable and can be influenced by new information and emotional connections. This offers hope that even deeply ingrained feelings of powerlessness can be shifted with appropriate inputs and support. Another potent strategy is to reframe challenges as opportunities. This is a classic cognitive reframing technique. Instead of viewing a setback as confirmation of powerlessness, it can be perceived as a learning opportunity or a chance to develop resilience. This isn’t about denying the difficulty but about altering one’s relationship to it. Finally, celebrate small victories. Acknowledge progress. Give credit for efforts. This reinforces positive behavior and helps to cultivate an internal sense of empowerment. The journey from feeling like an underdog to feeling empowered involves taking conscious steps to reclaim agency, build confidence, and connect with sources of strength, both internal and external.

Conclusion:

The exploration of the “Underdog’s Mind” reveals a complex psychological landscape. It’s clear that lacking power—being the underdog—isn’t just a label; it’s a psychological state that significantly influences choices and risk assessments. From the constrained decisions observed in scenarios like the “poor player” in a rigged Monopoly game to the intricate calculus of risk when resources feel scarce, the underdog’s mind navigates a unique and often challenging terrain. This journey has highlighted how such a state can lead to feelings of powerlessness, a heightened awareness of threats, and sometimes even a sense of resignation. Yet, it has also touched upon the remarkable human spirit, that persistent drive to strive and engage, even when the game feels decidedly rigged.

However, the narrative does not conclude there. Understanding these dynamics is the first step towards change. Recognizing how a lack of power can shape thinking and behavior allows for conscious efforts to mitigate those effects and foster a sense of empowerment, both individually and collectively. It’s about focusing on controllable factors, celebrating strengths and small wins, seeking support, and reframing challenges.

What are your thoughts on the underdog’s mind?

Have these dynamics resonated with your observations or experiences? Sharing insights and experiences can further illuminate this important topic. If this exploration has been valuable, consider sharing this article with others who might find it insightful. Let’s continue the conversation.

Leave a comment